Water Quality and Access in the Arizona–Mexico border

Summary:

A recent study by SWEHSC member Mónica D. Ramírez-Andreotta, PhD with Dr. Aminata Kilungo, PhD, explored how drinking water quality, community perceptions, and socioeconomic factors affect metalloid exposure and contribute to vulnerability. The study integrated the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) framework for a comprehensive understanding of the complexities surrounding water quality, access, and public health. The study found that many residents of Naco and Nogales rated their water around 7 out of 10, often considering it unsafe to drink. As a result, many rely on bottled water, especially since they also reported water shortages in the past month. This study highlights factors such as income, education, housing conditions, and employment status influence how individuals perceive water quality and affect their behaviors, including choosing bottled water or avoiding tap water.

What is the major issue with drinking water quality along the U.S.-Mexico border?

Access to clean and safe drinking water is a basic human right and an essential factor in public health. While reliable water supply and management systems are vital for the health and development of communities worldwide, it is estimated that 2.2 billion people do not have access to safe drinking water. Disparities in water access and quality are influenced by geographic, economic, and social factors, with people in disadvantaged areas often experiencing limited access to safe water. Arsenic and lead are two of the most common water contaminants that pose significant health risks. Though these contaminants have been studied at large, many studies fail to integrate socioeconomic factors that may also affect water quality and access.

The U.S.-Mexico border is a critical location with poor water quality and limited access. Due to its vast size and rapidly growing population, the region faces increasing risks from climate change, compounded by industrialization and socioeconomic challenges. Border communities are particularly vulnerable due to their proximity to harmful sites that release dangerous chemicals such as barium, lead, mercury, nickel, and zinc. These chemicals are considered metals and “metalloids”, or a mixture of metals and nonmetals.

What were the results of this study?

This study sought to answer three questions: 1) How do metal(loid) concentrations from various water sources differ? 2) How do sociocultural and economic factors influence community perceptions of water quality? 3) What are the additional potential pathways of exposure to metal(loid)s, in addition to drinking water, considered social determinants of health? Two surveys, one health survey and one environmental survey, were sent to individuals living in Nogales and Naco, Sonora, Mexico. In addition, a chemical water quality analysis of drinking water was sampled from wells, pipas (water tanks), and public water systems during monsoon season.

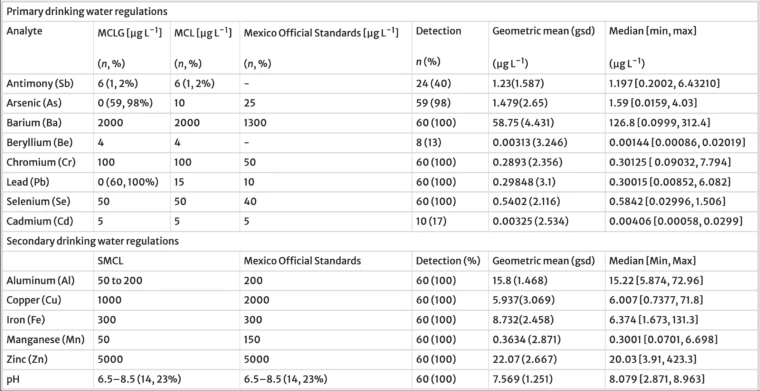

The table above shows the concentrations of certain metal(loids) measured in the study. Out of the 60 total water samples collected for a chemical water quality analysis, all 19 metal(loids) were detected. Eleven chemicals were detected with a 100% occurrence, meaning they were identified in all 60 samples, including barium, lead, copper, iron, and zinc. Though all levels detected were below the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and official Mexican drinking water standards, increased exposure can lead to adverse health outcomes. Nogales had higher concentrations of antimony, arsenic, chromium, aluminum, iron, and manganese, while Naco had higher concentrations of barium, copper, zinc, vanadium, silver, and cobalt.

As for the surveys, pipa users rated their water quality at 7.25, and public water users rated their water at 7.48 on a scale from 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest). They stated their water was dirty, tasted bad, was unfit for drinking, and could only be used for household chores. However, 75% of participants relying on pipas stated they were comfortable with drinking tap water, while only 5% of participants depending on public water were comfortable drinking tap water. 62% of all participants reported having insufficient water within the past month, causing them to turn to supplementing water from privately owned wells or purchasing bottled water. Heavy reliance on bottled water can place a significant financial burden on households, sometimes costing thousands of dollars annually. For vulnerable populations, this added expense can worsen existing socioeconomic hardships and deepen inequalities in access to safe and affordable drinking water.